Admission to university in China depends on scores in a nationwide exam called the National College Entrance Exam (NCEE), or Gaokao in Chinese (literally, “high test”). It is hard to underestimate how brutal this exam is for most students. It’s a nine-hour exam (spread over two or three days), and it basically chooses the fate of each student — for life. If you can’t get a high enough score, then you won’t get into university, and without university your life is likely to be far more limited. Think of the Gaokao as the SAT® or ACT, times a thousand. Everything depends on it. Applying for university mostly consists of sending them your score. And yes, you can re-take the exam if necessary, but because it’s only held once per year, well … let’s put it this way: one nickname for the test is “one-shot, one-kill.” In other words everything depends on one sitting of one test.

In North America, there is an ongoing debate about standardized testing, mainly centered around the idea that schools “teach to the test” in order to raise scores and boost funding. In China, everything is about the Gaokao. Once students hit high school (beginning at age 12), the focus on that exam soars. One thing that happens at around age 15 or 16 is one huge life-deciding choice: they must pick one of two “streams” that will decide their future career. Either they pick the “social science” stream, which emphasizes social sciences like history and geography plus a foreign language (usually English), or the “natural science” stream, which emphasizes advanced math and science. Both streams include math and Chinese.

Once that “stream” is chosen, students spend the next several years doing whatever it takes to master the subjects that will be on the Gaokao. The school year in China is far longer than in the West, at 245 days of the year (it’s well under 200 in the US), and as high school progresses the days get longer — as the Gaokao approaches it’s normal for high schoolers to attend school from 7am till 11pm. No, that’s not a typo, sixteen-hour days are utterly normal. They take regular classes in the daytime followed by evening sessions to cram in more learning. Yes, it’s exhausting. And yes, calling it “stressful” doesn’t even begin to cover it.

High school life is very different in China. Because of the focus on the Gaokao, little time is left over for socializing, dating, gaming or just generally slacking. Forget skipping class. The whole thing is a family affair, with everyone working to support the student. If you’re a working-class family, a child who graduates university and gets a good office job may well be able to support the whole family. On the day of the test, students often board a bus at their high school and a massive crowd surrounds them — their families, waving, cheering and wishing their best.

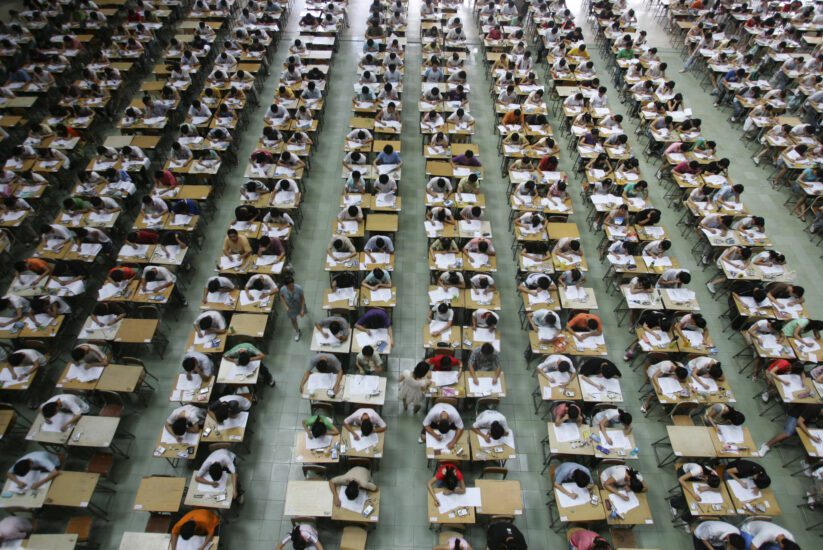

Unsurprisingly, there are many stories of psychological and physical collapse due to the pressure. It doesn’t help that no allowances are made for sickness or learning exceptionalities. It is a national event that dominates the media when it takes place. After all, it might involve nine or ten million students taking the exam at the same time. Talk about competition!

There are essay questions on the Gaokao in addition to the standard study-based questions. Here’s one example from a recent Gaokao (note that the Chinese school system places a heavy emphasis on what we would call “building character”):

“Everybody has tough and soft spots in his/her heart. Whether you can reach an inner harmony depends on how you balance the toughness and softness. Please choose an angle and write an essay on this topic in 800 words or more.”

In previous decades, the rate of university attendance was extremely low, around 20% of the population. But perhaps because university is seen as a path to raising living standards, the rate of attendance has risen over the years — the exact number is hard to determine for certain but it appears to be around 50% or so.

There are many problems with the Gaokao. In many ways its rigidity makes it demonstrably unfair, for one thing. Indeed there has been debate in China for years about whether to switch to a more American-style system that allows greater room for creativity and imagination over rote memorization, but there’s little sign that any change will take place.

Chinese teenagers see portrayals of American high schools in movies and on TV, and it usually seems incredibly foreign to them — so much socializing, so much fooling around, so much talking back to the teachers! One wonders what American students would think of a day in the life of their Chinese equivalents.